Finite Element Analysis (FEA): A Comprehensive Guide to Modern Engineering Simulation

In the realm of modern engineering, the ability to predict how designs will perform under various real-world conditions is paramount. This is where Finite Element Analysis (FEA) emerges as an indispensable tool. FEA is a powerful numerical method employed by engineers across virtually all disciplines to simulate the behavior of physical systems and components. By transforming complex designs into a series of smaller, manageable elements, FEA allows for the detailed analysis of stresses, strains, heat transfer, fluid flow, and much more, long before a physical prototype is ever built.

From the robust structures of aerospace components to the intricate circuits of microelectronics, FEA provides critical insights, enabling optimization, reducing development costs, and significantly accelerating the design cycle. This comprehensive guide will delve into the core principles, processes, applications, and profound benefits of Finite Element Analysis, offering a foundational understanding for engineers, students, and technology enthusiasts alike.

What is Finite Element Analysis (FEA)?

Finite Element Analysis (FEA) is a computational method used to solve complex engineering problems that are often intractable by analytical means. At its heart, FEA is a numerical technique for finding approximate solutions to partial differential equations (PDEs), which describe a wide range of physical phenomena such as structural mechanics, heat transfer, electromagnetism, and fluid dynamics.

The core concept behind FEA involves discretizing a continuous, complex system (like a mechanical part or an entire structure) into a finite number of smaller, simpler, interconnected geometric units called finite elements. These elements are typically small, simple shapes like triangles, quadrilaterals, tetrahedrons, or bricks. The points where these elements connect are known as nodes.

Instead of solving the governing equations for the entire complex domain at once, FEA solves these equations for each individual element. The behavior of each element is described by a set of algebraic equations. These individual element equations are then assembled into a larger system of equations that represents the entire structure. By solving this global system of equations, engineers can determine approximate values of physical quantities (like displacement, stress, temperature, or velocity) at the nodes, and subsequently, throughout the entire system. This approximation becomes more accurate as the number of elements (and thus nodes) increases, effectively capturing the nuanced behavior of the system with greater fidelity.

The Fundamental Principles Behind FEA

Understanding the fundamental principles of FEA is crucial for appreciating its power and limitations. The process typically involves several key steps:

Discretization (Meshing)

The first and often most critical step in any FEA project is discretization, commonly known as meshing. The continuous domain of the physical object is divided into a finite number of small, interconnected elements. The choice of element type and mesh density significantly impacts the accuracy and computational cost of the analysis. Common element types include:

- 1D Elements: Beams, rods, trusses (for slender structures).

- 2D Elements: Shells, plates, membranes (for thin structures or planar problems).

- 3D Elements: Tetrahedrons, hexahedrons (bricks), pyramids, wedges (for solid bodies).

Mesh quality, including element shape, aspect ratio, and Jacobian, is vital. Poor mesh quality can lead to inaccurate results or convergence issues. Techniques like adaptive meshing can automatically refine the mesh in areas of high stress gradient to improve accuracy efficiently.

Governing Equations & Variational Principles

The physical behavior of the system (e.g., structural deformation, heat flow) is governed by specific partial differential equations (PDEs). In FEA, these PDEs are often converted into an equivalent weak form using variational principles (like the Principle of Minimum Potential Energy for structural mechanics) or weighted residual methods (like the Galerkin method). This transformation allows for less stringent requirements on the continuity of the solution, making it easier to find approximate solutions.

Formulation of Element Stiffness Matrices

For each finite element, its contribution to the overall system behavior is quantified. This typically involves defining interpolation or shape functions that describe the field variable (e.g., displacement) within the element based on its nodal values. These shape functions, along with material properties and element geometry, are used to derive an element-specific matrix (e.g., a stiffness matrix in structural analysis, or a conductivity matrix in thermal analysis) that relates nodal forces to nodal displacements, or nodal heat fluxes to nodal temperatures.

Assembly of Global System Equations

Once the individual element matrices are formulated, they are systematically assembled into a global system matrix that represents the entire structure. This process ensures continuity and equilibrium across element boundaries. For structural problems, this results in a global system of linear algebraic equations, often represented as [K]{U} = {F}, where:

- [K] is the global stiffness matrix, encompassing the material and geometric properties of the entire structure.

- {U} is the global vector of unknown nodal displacements.

- {F} is the global vector of applied external nodal forces.

For other physics, similar equations exist (e.g., a global conductivity matrix for heat transfer).

Application of Boundary Conditions

Before solving the global system of equations, appropriate boundary conditions (BCs) must be applied. Boundary conditions represent the interaction of the system with its environment. Common types include:

- Dirichlet Boundary Conditions (Essential BCs): Specify the value of the field variable (e.g., fixed displacements, prescribed temperatures).

- Neumann Boundary Conditions (Natural BCs): Specify the derivative of the field variable (e.g., applied forces, heat fluxes).

These conditions are crucial for obtaining a unique and physically realistic solution. They often involve modifying the global system matrix and force vector.

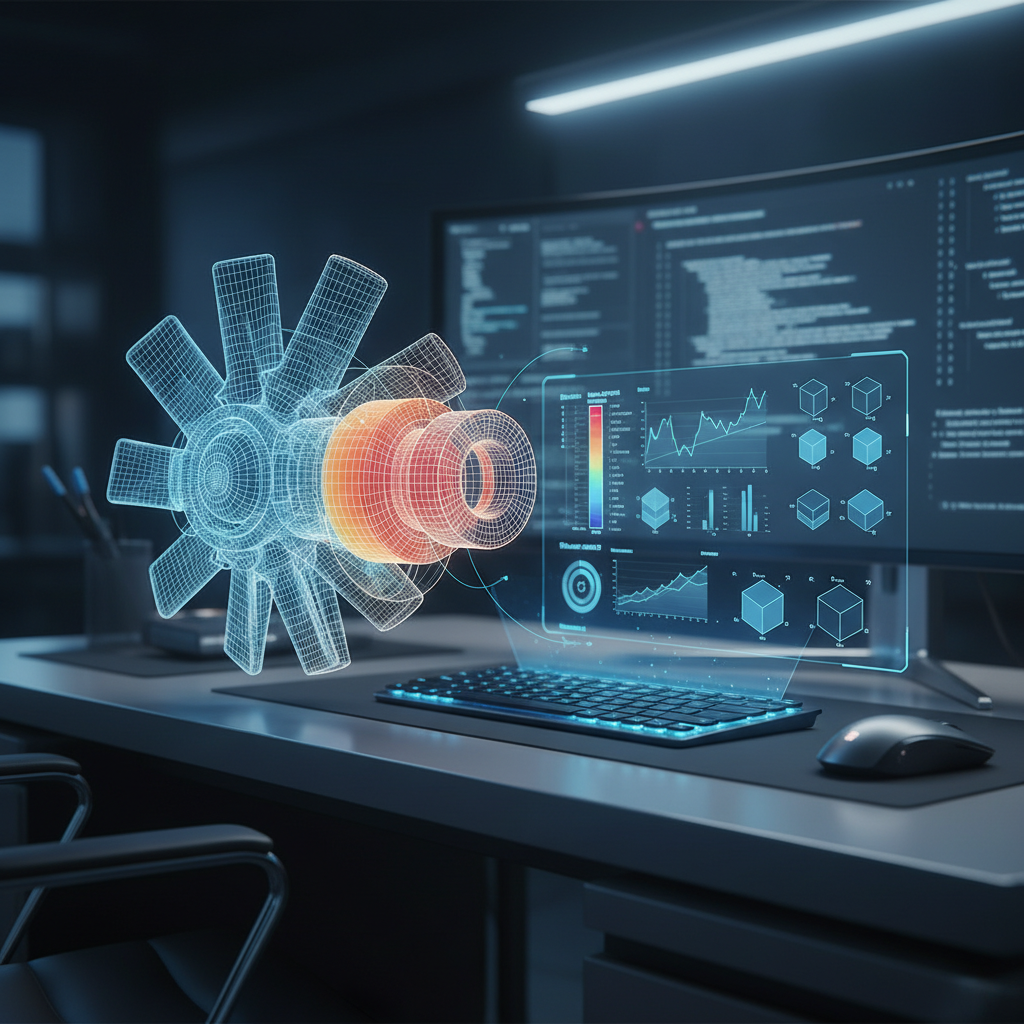

The FEA Process: From CAD to Results

A typical FEA workflow can be broken down into three main phases:

Pre-processing

This is the setup phase where the engineering problem is translated into an FEA model. Key steps include:

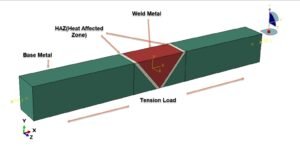

- Geometry Creation or Import: Start with a CAD model of the component or assembly. Complex geometries may need simplification to remove small features that are computationally expensive but don’t significantly affect the overall analysis.

- Material Properties Definition: Assign appropriate material properties (e.g., Young’s Modulus, Poisson’s Ratio, yield strength for structural analysis; thermal conductivity, specific heat for thermal analysis).

- Meshing: Generate the finite element mesh over the geometry. This involves choosing element types, size, and refinement strategies. Good mesh generation is critical for accurate results.

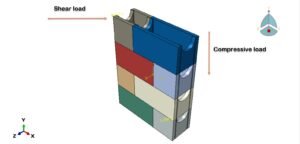

- Loading and Boundary Conditions: Apply all relevant loads (forces, pressures, temperatures, accelerations) and boundary conditions (fixed supports, prescribed displacements, heat sources/sinks). These represent the real-world operational environment.

- Contact Definitions: For assemblies, define how different parts interact (e.g., bonded, sliding, no separation).

Solving

Once the pre-processing is complete, the FEA solver takes over. This phase involves setting up and solving the global system of equations derived from the discretized model and applied boundary conditions. The type of solver used depends on the nature of the analysis:

- Linear Static: For problems where materials behave linearly elastically, deformations are small, and loads are static.

- Non-linear: For large deformations, non-linear material behavior (plasticity, hyperelasticity), or non-linear contact.

- Transient/Dynamic: For time-dependent problems, such as impact, vibration, or time-varying thermal loads.

- Modal Analysis: To determine natural frequencies and mode shapes of a structure.

The solver performs numerous calculations, often involving large sparse matrix inversions, to determine the unknown field variables (e.g., nodal displacements) at each node.

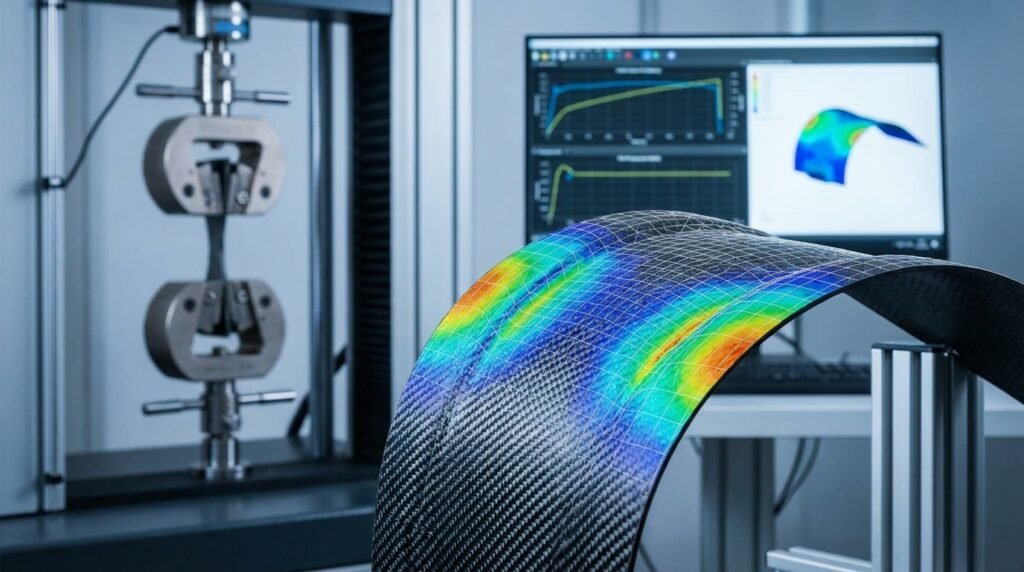

Post-processing

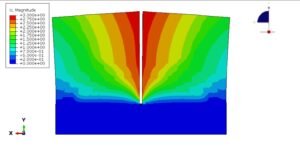

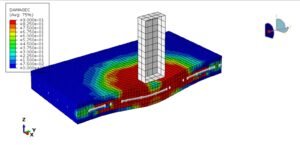

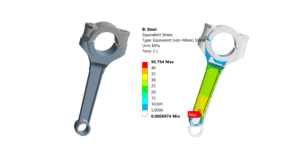

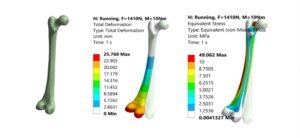

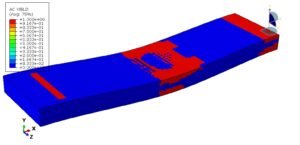

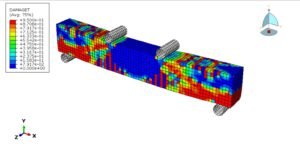

The final phase involves interpreting and visualizing the results obtained from the solver. Raw numerical data is transformed into easily understandable graphical representations:

- Contour Plots: Show the distribution of variables like stress, strain, temperature, or pressure across the model.

- Deformation Plots: Visualize the exaggerated deformation of the structure under load, indicating areas of high displacement.

- Vector Plots: Illustrate directional quantities like heat flux or fluid velocity.

- Animations: For dynamic or transient analyses, animations can show the time-dependent evolution of a phenomenon.

- Tabular Data: Extract specific numerical values at points of interest.

Effective post-processing is crucial for engineers to gain insights, identify critical areas, validate designs, and make informed decisions.

Key Applications of FEA Across Industries

FEA’s versatility makes it applicable across an enormous range of engineering disciplines and industries:

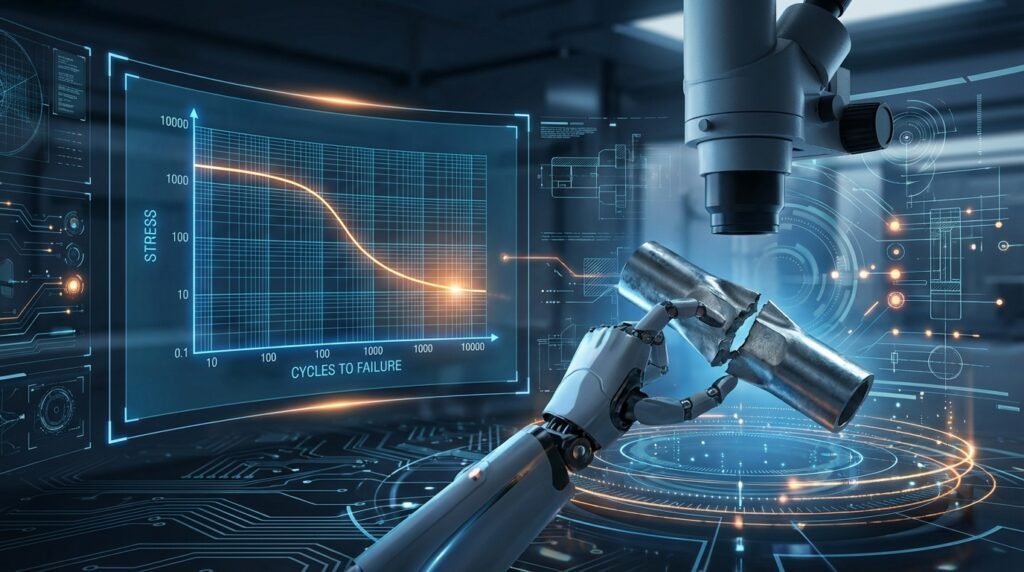

Structural Analysis

This is perhaps the most common application of FEA, used to predict how structures and components react to forces, pressures, and other loads. It covers:

- Stress and Strain Analysis: Identifying areas of high stress concentration to prevent failure.

- Deflection and Displacement: Ensuring a design meets stiffness requirements.

- Fatigue Analysis: Predicting product life under cyclic loading.

- Buckling Analysis: Assessing the stability of slender structures under compression.

- Vibration and Modal Analysis: Determining natural frequencies and mode shapes to avoid resonance.

Examples: Designing aircraft wings, automotive chassis, bridge structures, biomedical implants, heavy machinery, consumer electronics enclosures.

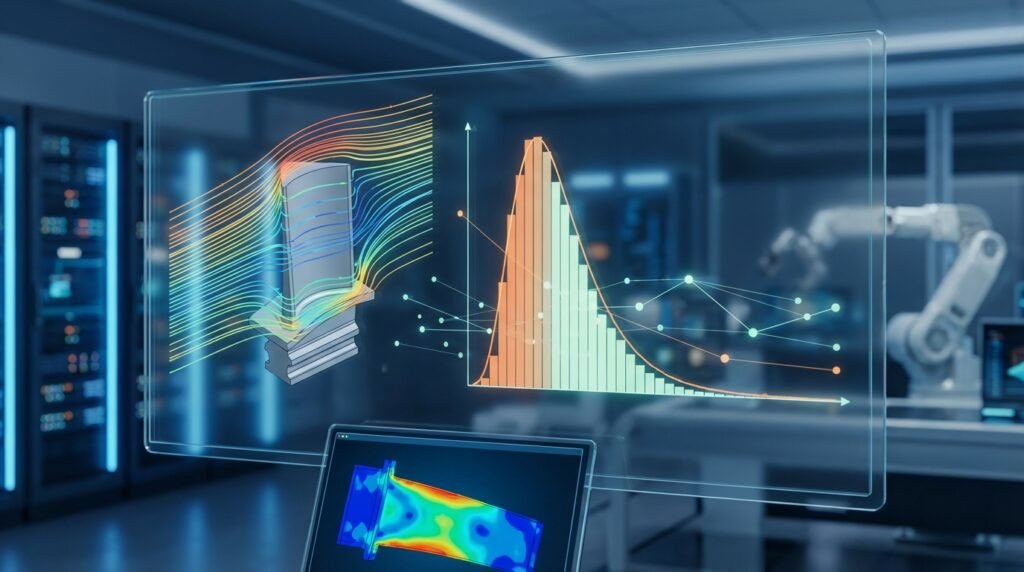

Thermal Analysis

FEA can simulate heat transfer phenomena, including conduction, convection, and radiation. This is vital for managing temperatures in systems:

- Temperature Distribution: Understanding how heat spreads through a component.

- Thermal Stress: Analyzing stresses induced by temperature gradients.

- Thermal Cycling: Simulating repeated heating and cooling effects on material fatigue.

Examples: Cooling systems for electronic devices, engine thermal management, heat exchangers, industrial furnaces, power plant components.

Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

While often a separate specialized field (Computational Fluid Dynamics, CFD), FEA principles can be applied to fluid flow problems. When coupled with structural analysis, it enables Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI) simulations.

- Flow Patterns: Visualizing how fluids move through or around objects.

- Pressure Drop: Calculating pressure losses in pipes or channels.

- Lift and Drag: Quantifying aerodynamic or hydrodynamic forces.

Examples: Aerodynamics of vehicles, blood flow in arteries, pipeline design, ventilation systems, turbine performance.

Electromagnetics

FEA is used to analyze electric and magnetic fields, crucial for the design of electrical components:

- Field Distribution: Mapping electric and magnetic field strengths.

- Inductance/Capacitance Calculation: Essential for circuit design.

- Losses: Predicting eddy current or hysteresis losses in materials.

Examples: Electric motors, generators, transformers, sensors, antennas, high-frequency circuits.

Multiphysics Simulations

Many real-world problems involve interactions between different physical domains. FEA tools increasingly offer multiphysics capabilities, allowing engineers to simulate coupled phenomena such as:

- Thermal-Structural: Heat causing expansion and stress.

- Thermoelectric: Electrical current generating heat.

- Fluid-Structure Interaction (FSI): Fluid forces deforming a structure, and the deformed structure affecting fluid flow.

Examples: MEMS devices, medical devices, tires, turbine blades, complete vehicle systems.

Benefits of Implementing FEA in Engineering Design

The adoption of Finite Element Analysis offers a myriad of benefits that significantly enhance the engineering design and development process:

- Reduced Physical Prototyping and Testing: By simulating performance digitally, engineers can drastically cut down on the number of expensive and time-consuming physical prototypes required, leading to substantial cost and time savings.

- Faster Design Iterations and Optimization: FEA allows for rapid testing of multiple design variations and material choices. This accelerates the design cycle, enabling engineers to quickly identify optimal configurations that meet performance, weight, and cost targets.

- Improved Product Performance and Reliability: Detailed insights into stress, strain, temperature, and other critical parameters enable engineers to identify potential failure points early in the design phase. This leads to more robust, reliable, and higher-performing products.

- Cost Savings: Beyond prototyping, FEA helps optimize material usage, reduce warranty claims due to early failure, and prevent costly design errors from reaching manufacturing.

- Failure Prediction and Prevention: FEA can predict where and how a component might fail under various loading conditions, allowing for proactive design modifications to enhance safety and durability.

- Virtual Experimentation: Simulating conditions that are difficult, dangerous, or impossible to replicate physically (e.g., extreme temperatures, high-speed impacts) provides invaluable data.

- Deeper Understanding of Product Behavior: FEA provides a detailed, element-by-element view of how a product behaves internally, offering insights that might be impossible to obtain from physical testing alone.

Challenges and Considerations in FEA

While immensely powerful, FEA is not without its challenges and requires careful consideration:

- Mesh Quality Sensitivity: The accuracy of FEA results is highly dependent on the quality and density of the finite element mesh. Poorly constructed meshes can lead to inaccurate, misleading, or even non-convergent solutions.

- Material Model Complexity: Accurately representing complex material behaviors (e.g., plasticity, viscoelasticity, hyperelasticity, anisotropy) can be challenging and requires precise material data, which isn’t always readily available.

- Computational Resources: High-fidelity FEA models, especially those involving non-linear or transient multiphysics simulations, demand significant computational power (CPU cores, RAM) and time.

- Solver Convergence Issues: Non-linear analyses, in particular, can suffer from convergence problems, where the solver fails to find a stable solution. This often requires significant expertise to troubleshoot and resolve.

- Interpretation of Results (Garbage In, Garbage Out): The accuracy of FEA output is only as good as the input. Incorrect boundary conditions, loads, or material properties will lead to erroneous results. Expertise is needed to correctly interpret and validate the simulation output against physical principles or test data.

- User Expertise Required: Performing effective FEA requires a solid understanding of engineering mechanics, numerical methods, and the specific FEA software. It’s not a ‘black box’ tool, and inexperienced users can easily misapply it.

The Future of Finite Element Analysis

The landscape of FEA is continuously evolving, driven by advancements in computing power, algorithms, and artificial intelligence:

- Integration with AI and Machine Learning: AI is being used to automate meshing, optimize design parameters, predict material properties, and even accelerate solver performance by learning from past simulations.

- Cloud-Based FEA: The shift to cloud computing makes high-performance computing resources more accessible, allowing smaller companies to run complex simulations without significant upfront hardware investment.

- Digital Twins: FEA is a critical component in the creation of digital twins – virtual replicas of physical assets that can simulate real-time performance and predict maintenance needs.

- Integration with Additive Manufacturing: FEA is crucial for optimizing designs for 3D printing, enabling engineers to create complex geometries that were previously impossible, while ensuring structural integrity.

- Enhanced Multiphysics and Multiscale Capabilities: Future FEA will offer even more seamless and robust simulations of coupled physical phenomena and the ability to link models from different scales (e.g., atomic to macroscopic).

Conclusion

Finite Element Analysis has cemented its position as an indispensable pillar of modern engineering. By providing a powerful virtual testing ground, FEA empowers engineers to design, analyze, and optimize products with unprecedented speed and accuracy. While it presents its own set of challenges, continuous advancements in computational power and methodology ensure that FEA will remain at the forefront of innovation, driving the development of safer, more efficient, and more reliable products across every industry.